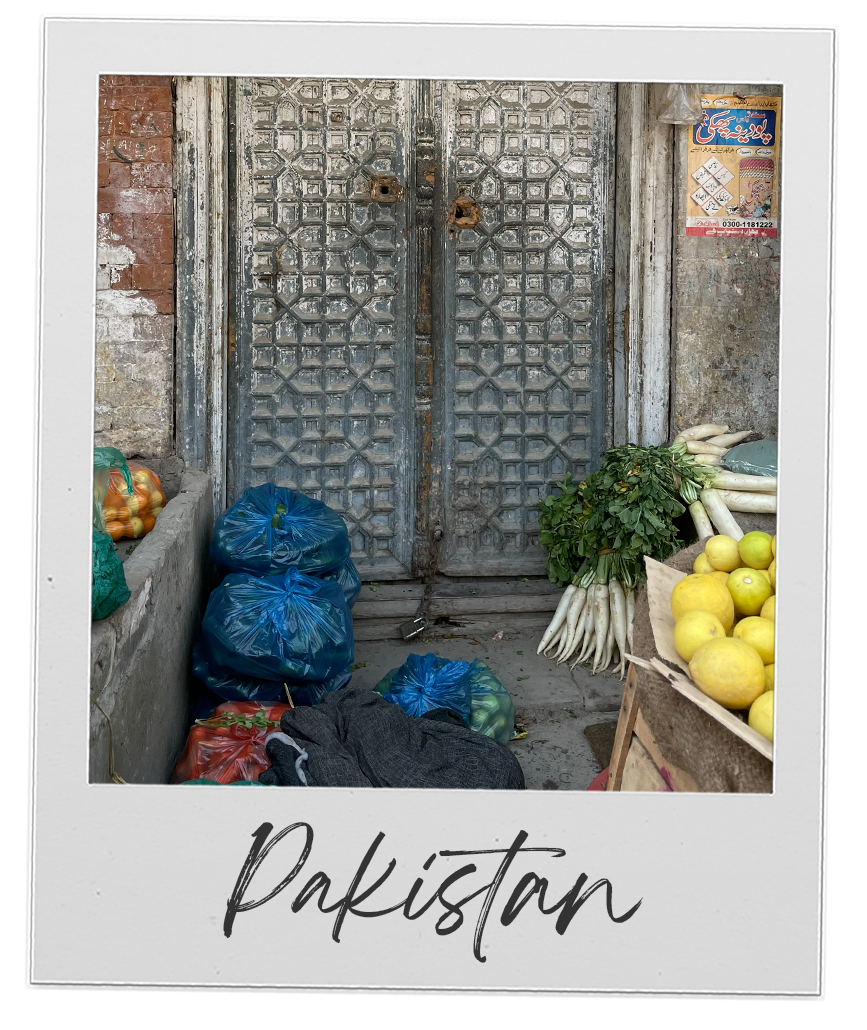

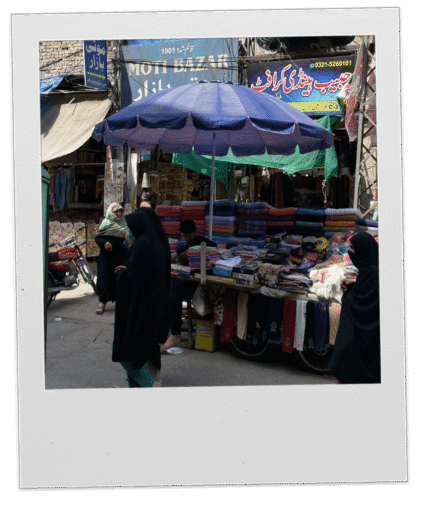

Pakistan

There are nearly 8.5 million migrant workers working across different regions of Pakistan, which includes both internal and foreign migrant workers. Forty-five per cent of these workers are engaged in informal activities including day labourers, construction workers, domestic helpers, factory workers, informal restaurants and beauty salons.

The domestic service sector is one of the largest informal employment sectors in Pakistan where there is an absence of labour protections and economic security. Middle and upper-class households employ women domestic workers, primarily Pakistani domestic workers. However, there are several women workers groups of migrant origin involved in the domestic care industry. Pakistan has become an employment destination for Migrant Filipino Domestic Workers (MFDW), who constitute one of the largest groups among the estimated over 2,000 Filipinos living in Pakistan and of the over 1,000 Filipinos holding a working visa.

There is low participation of women in the formal sector, a widening gender pay gap, and a concentration of women in low-paid and low-skilled jobs. This is coupled with a lack of legal protection for women working in the informal sector (agriculture, domestic and home-based work) to whom the federal and provincial labour laws

and regulations do not apply. There is also a lack of labour law and social security programmes, such as wage protection and maternity leave, for working women in the informal economy.

Pakistan has received a mass influx of people fleeing conflict. The Afghan community is among the largest among undocumented migrants living in the country (1.7 million according to recent estimates), followed by combined populations of Bengali ethnic group, and nationals from Bangladesh and Burma

Migration and displacement

Labour and migrant workers

There are nearly 8.5 million migrant workers working across different regions of Pakistan, which include both internal and foreign migrant workers. Forty-five per cent of these workers are engaged in informal activities including day labourers, construction workers, domestic helpers, factory workers, informal restaurants, and beauty salons.

For this research 22 semi-structured interviews were conducted, predominantly in Islamabad, with adult migrant women with different skill levels, nationalities, and migration experiences.

What we found

Diversity

The majority of participants consisted of highly skilled and educated migrant women of diverse nationalities who migrated from the Philippines, Canada, China-Korea, Uganda, Germany, Egypt, and Somalia. They worked in formal sectors, i.e., teaching and as development professionals in international NGOs/UN agencies. They came to Pakistan for different reasons: family reunification, marriage, independent work and for education and professional opportunities. A significant proportion, mainly from the Philippines, worked as live ins in the domestic care sector. Afghan participants worked in the semi-skilled sector as self-employed workers in the service industry, such as beauty salons and carpet-weaving. A few research participants work independently as business owners or in service industries.

Challenges

Gender-based discrimination in Pakistan was not openly reported by the migrant women workers who participated in this study, despite those who are married to a Pakistani reporting instances of clashing gender norms. Nearly all describe their living and working conditions in positive terms.

However, lack of official documents created daily challenges. Many migrant workers detail instances of obstacles that they encountered in their daily life because they are not in possession of the national ID card.

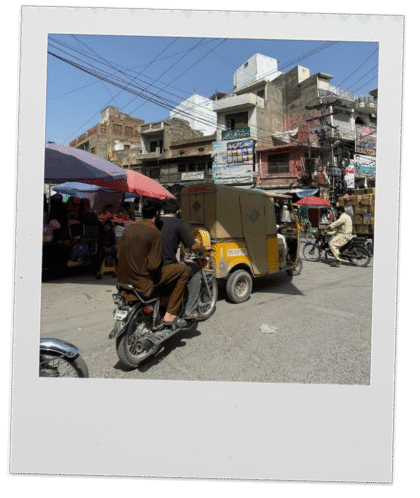

The women have relatively high levels of mobility. Despite the diversity of life and work experiences, including the type of accommodation and living arrangements, most women said that they move around the city freely, using cars or taxis, that they go to restaurants, malls, and markets. For migrant domestic workers their process of acquainting with the host country and ‘going out’ to public spaces is filtered by the family they live with, and, to a certain extent, necessarily hampered by their home-based work.

Their coping strategies consisted of making choices, taking actions, and creating narratives that mitigated the hardships of their situation in different realms, from the domestic to the workplace.

Culture and conflict

This research investigated the value of culture to women in conflict settings, seeking to understand gendered economic exclusion and its relationship to peacebuilding, economic agency and empowerment. It used a cultural mapping methodology to explore how communities of women rely on coded and tacit knowledge to rebuild their lives and to understand how cultural practices continue to exist and resist in these challenging contexts.

What we found

Autonomy and independence

The ability to generate an income through crafts gave the women greater autonomy in decision making, particularly in relation to marriage. Generating a sustainable livelihood is a short way of pushing back against early marriage. For some of the women who were already married it led to a greater respect from their spouse in their marriage.

Income generated from commercialising research gives them a much-needed financial boost to invest in raw material and build their craft businesses independently, pushing back on marriage through the argument for an economic independence.Feminist movements

Feminist movements in Pakistan which support women’s ambitions to work and build incomes and careers have engaged with this project. Some of them are part of the focus groups and have cascaded this craft-based approach to sustainable incomes, through discussion groups and training, widely in their region of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa allowing for wider outreach and impact footprint of the project.

Reaching the marginalised

Women from hard to access remoter regions must be included in an equitable manner in research. This includes funding their travel in safe and appropriate manner, which is agreeable with them and their family members. Provision of childcare of work settings in which young children are welcome and catered to is important.

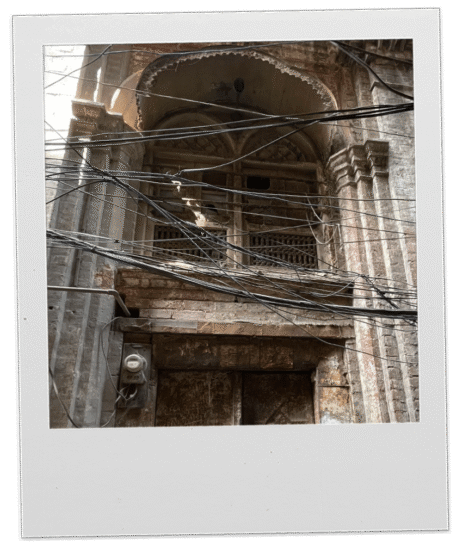

Protecting heritage

Craft making, and practices which are embedded within community structures should be valued and supported to enhance value to makers and their families. There is very limited documentation or literature of cultural practices in this context and a real risk that some knowledge may be lost. The documentation of such cultural practices through processes led by the communities themselves should be prioritised. Limitations of access to materials and spaces should be clearly built into policy and programming for economic development.

Concepts of heritage that are linked to ecologies of making and landscapes of production must feature in cultural development. Long standing histories of making, the made, the maker, the language, the environment, and patterns of making across seasons intersects with project design and methodology and research outcomes. Longevity of practices which are resilient, and their nuances are worthy of mapping and for learning from.

Animation

People On The Move

Resources

The Story of Shoka

In the Upper Chitral region of Pakistan, communities in Harchin and Broke practice distinct craft traditions tied to their environment and daily life. In Broke, apricot wood is carved into musical instruments like the sitar, a craft now carried forward by only two artisans known as Sitar sauziyek. The sitar features in a local folktale […]

The Story of Sitaar

In Broke, Laspur Valley, Upper Chitral, Pakistan, apricot trees are grown widely. The fruit is used in various forms, and the wood is carved into utensils and musical instruments, including the sitar. The carving is traditionally done by a few skilled men known as sitar sauziyek. The sitar is also central to local storytelling, such […]

The Story of Rope

In Baleem, Laspur Valley, Pakistan, families rear yaks and use their wool to make ropes and tents. Yak hair is plucked once a year, typically by men, and spinning the wool into rope is often a collaborative family activity. Due to limited market availability, most families make their own ropes, which are valued for their […]

The Story of Qaleen

In Laspur Valley, Upper Chitral, Pakistan women traditionally weave Qaleen carpets, often given as gifts or dowry and used in households. This craft, passed down through generations, is demanding and locally referred to as “Dhagay ki dewaar” (wall of thread). Carpet weavers are known as Qaleen Korak Aurat, reflecting their dual roles in domestic and […]

The Story of Khamta

This video presents an overview of khamta weaving, a traditional craft practiced in Rajjar, Charsadda, Pakistan. Khamta weaving has a long history in the region and is carried out in homes, where most families have one or two handlooms. While men historically managed the weaving, women have also contributed to the process due to the […]

The Story of Dhaga

This video documents traditional craft practices in Harchin, Laspur Valley, Upper Chitral, Pakistan. It highlights the role of older women, particularly grandmothers, in spinning thread – a communal activity where one individual can produce enough thread for nearly four carpets in a single night. Livestock such as sheep, goats, and yaks are commonly reared by […]

The Story of Astari

This video delves into the intricate embroidery traditions passed down through generations of women in the Gandhara region. More than just a craft, embroidery is a form of social bonding, where women gather after daily chores to sew, sing, and share stories – often finishing each other’s work. Seasonal garments like embroidered ‘palos’ and salampur […]

Forced Displacement: Afghanistan and Pakistan

In this video, Afghan refugee children reflect on their disrupted education during COVID-19 and how the Sikhao Saathi program helped them get back to learning. Despite lacking Pakistani ID cards, many have rejoined government schools – some already in Grade 6 – and even discovered a passion for teaching. They share the ongoing challenges of […]

Reconstruction of Kashmir and the role of Islam

This chapter looks at the lived realities of Islam in Kashmir. It looks at the Muslim women in Kashmir who struggle to cope in a post conflict environment. Conflict is known to present an unequal burden on women. This chapter examines the impact of conflict on women in Kashmir. Kashmiri Muslim women were traditionally protected […]

Interconnected & Multiple Crisis: Gendered Displacement & Cross-Border Migration Across Afghanistan & Pakistan

A presentation delivered at IMISCOE Spring Conference 2024. The history of Afghanistan & Pakistan has shared ongoing socio-political instability, armed conflicts, environmental catastrophes and economic crises. Almost 2 million Afghan live in Pakistan. Between 2002 and 2021, over 5 million refugees returned home, while nearly 3.5 million Afghans are presently internally displaced. Data were collected […]

Pakistan country briefing

The brief focuses on Pakistan and the gendered dynamics of international labour migration as a case study that expands our knowledge of South-South migration and reveals the complexity and context of gendered migration patterns and dynamics. In doing so, this brief aims to advance a gender sensitive understanding of interactions between economic, social and cultural […]

Research and knowledge exchange: notes from South Asian neighbourhoods

This publication underlines that the delivery of excellent and ethically centred knowledge exchange and research collaborations with a wide range of partners, draws on an extraordinarily wide range of skills, competencies, and resources. We need to be careful and supportive of the people leading this work, as well as our collaborative partners. This is particularly […]

Return, Reintergration and Political Restructuring

Previous research on return migration has mainly covered return to political and economically stable countries. Furthermore, the literature predominantly focusses on economic reasons for return. Much less is known about the gendered experience of return migration to conflict-affected contexts, and how this relates to development, gender equality, justice and inclusive peace. This research project explores […]

“I was born here”: Children’s participation and refugee education in Pakistan

Over the last four decades, there have been several waves of movement across the borders due to recurring conflict in Afghanistan, as well as internal displacement within the country due to conflict and natural disaster. Pakistan remains one of the five largest refugee-hosting countries in the world; as of June 2022, an estimated 1.3 million […]

Educating beneficiaries on micro-finance loans: Workshop report with Kashf Foundation

This meeting report details how the Kashf Foundation workshop effectively fulfilled its objective of educating beneficiaries on the intricacies of securing loans from Kashf Foundation. Participants departed with a heightened comprehension of microfinance and the nuanced facets of borrowing. This bolstering of financial literacy equips beneficiaries to make informed and prudent financial choices, harnessing available […]

The Culture and Conflict Project – Forum with Policy Makers Report – PAIMAN

PAIMAN have been engaging and advocating with policy makers since 2011 regarding inclusion of women in policy frameworks, decision making and implementation pertaining to peace, security and disaster. As a result Provincial Disaster Management Authority (PDMA) of Khyber Pukhtunkhwa with the active support of PAIMAN now has gender-responsive Relief and Recovery (R&R) policy as compared […]

Conflict and Culture Project Impact Report – Pakistan – Paiman Trust

PAIMAN Alumni Trust has played a vital role as one of the key implementers in the Gender Justice and Security Hub’s Culture and Conflict project within Pakistan. Focusing its efforts on artisans in Peshawar, Charsadda, and Swat, PAIMAN has chosen to work in regions that have been conflict-prone and continue to grapple with the aftermath […]

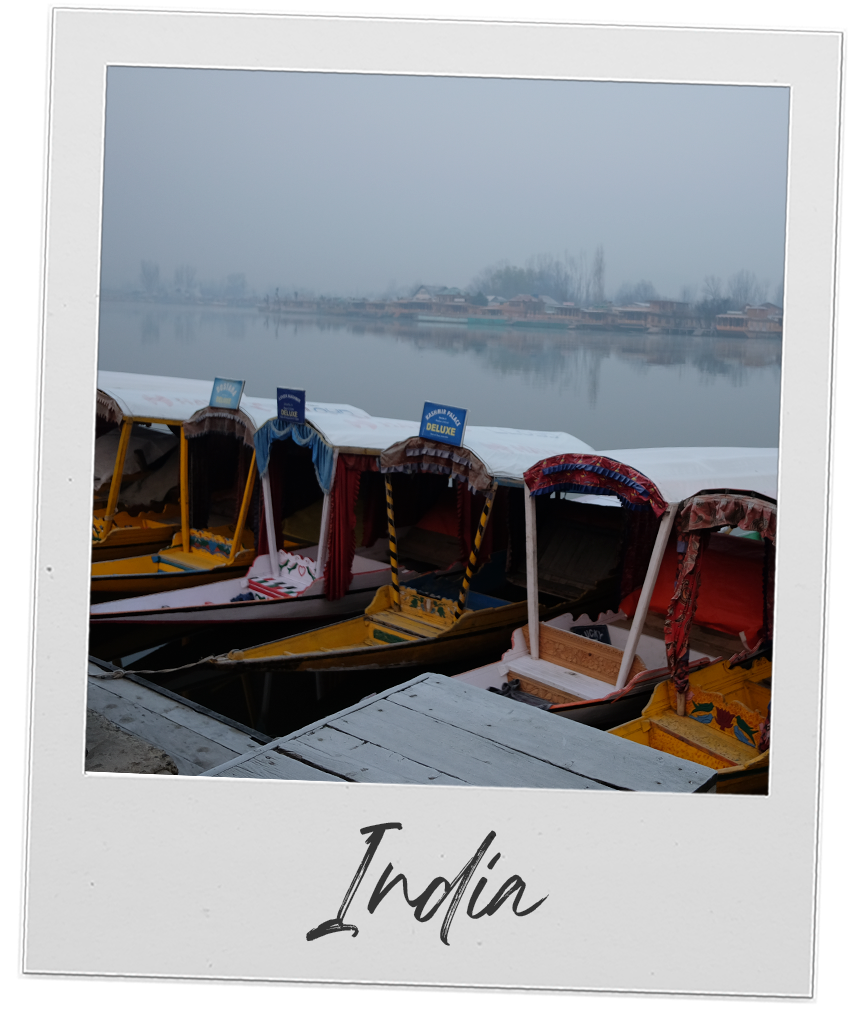

Gendered Dynamics of International Labour Migration: Migrant Women Working in Pakistan

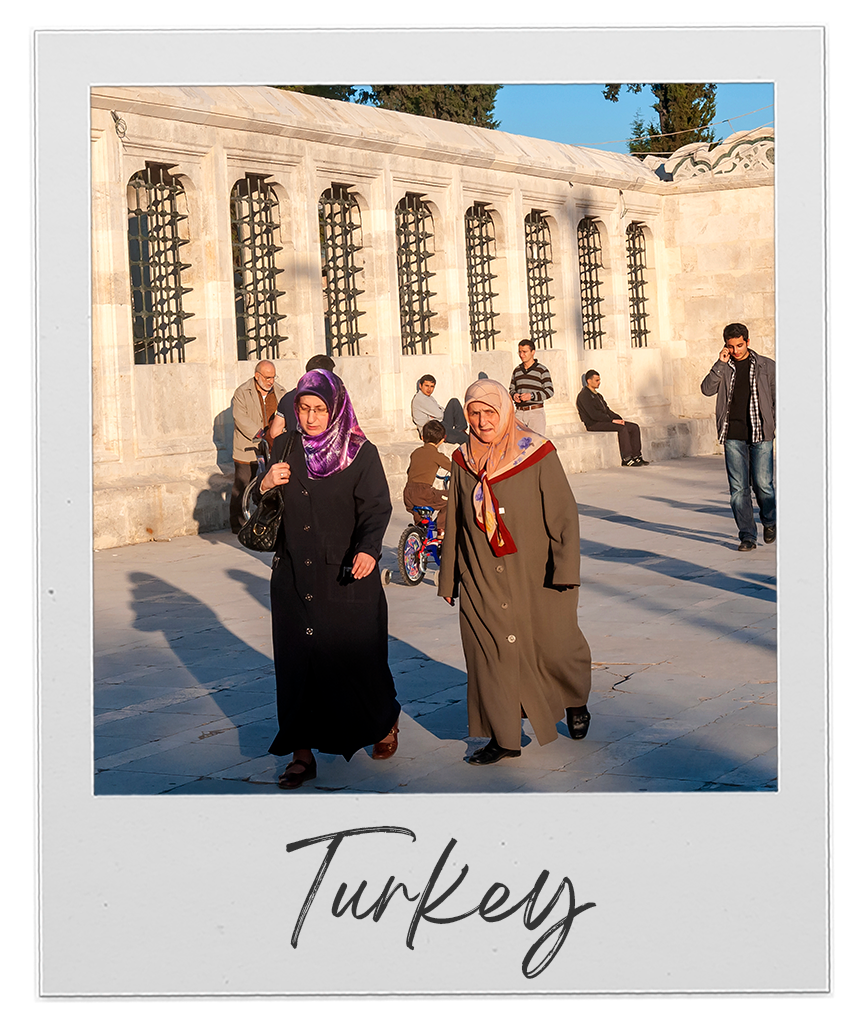

This study is part of a larger multi-country research project ‘Gendered Dynamics of Labour Migration’ involving three other countries and main cities, in addition to Islamabad in Pakistan, Istanbul in Turkey, Beirut in Lebanon,and Erbil in Kurdistan Iraq (KRI). The project set out to elaborate a gender-sensitive understanding of the interaction between economic and socio-cultural […]