Kurdistan

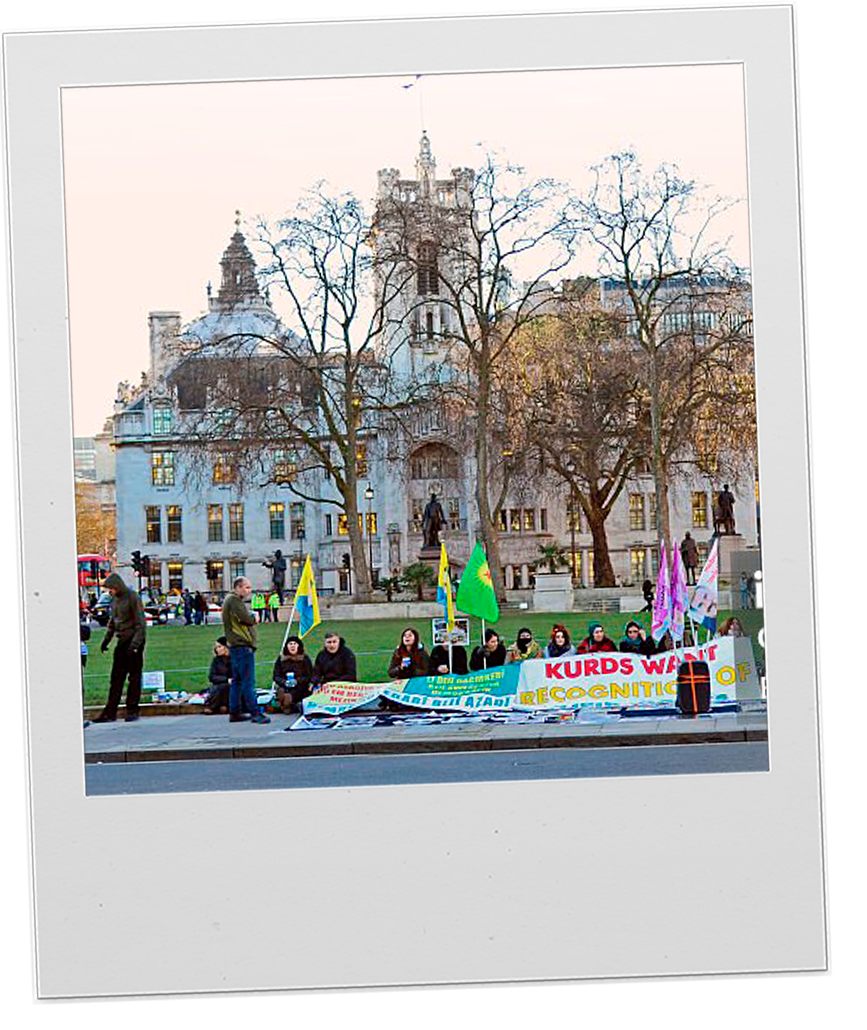

The Kurdish community not only constitutes one of the largest stateless nations in the world, but also one of the largest diaspora communities. Despite this , there is a lack of statistical data on the Kurdish population in Europe. What data there is, is unreliable due to the way countries register migrants according to their nationality, not their ethnic affiliations. For this reason, Kurds are registered as ‘Turkish’, ‘Iranian’, ‘Iraqi’ and ‘Syrian’ when they arrive in Europe, imposing upon them an unacceptable national identity.

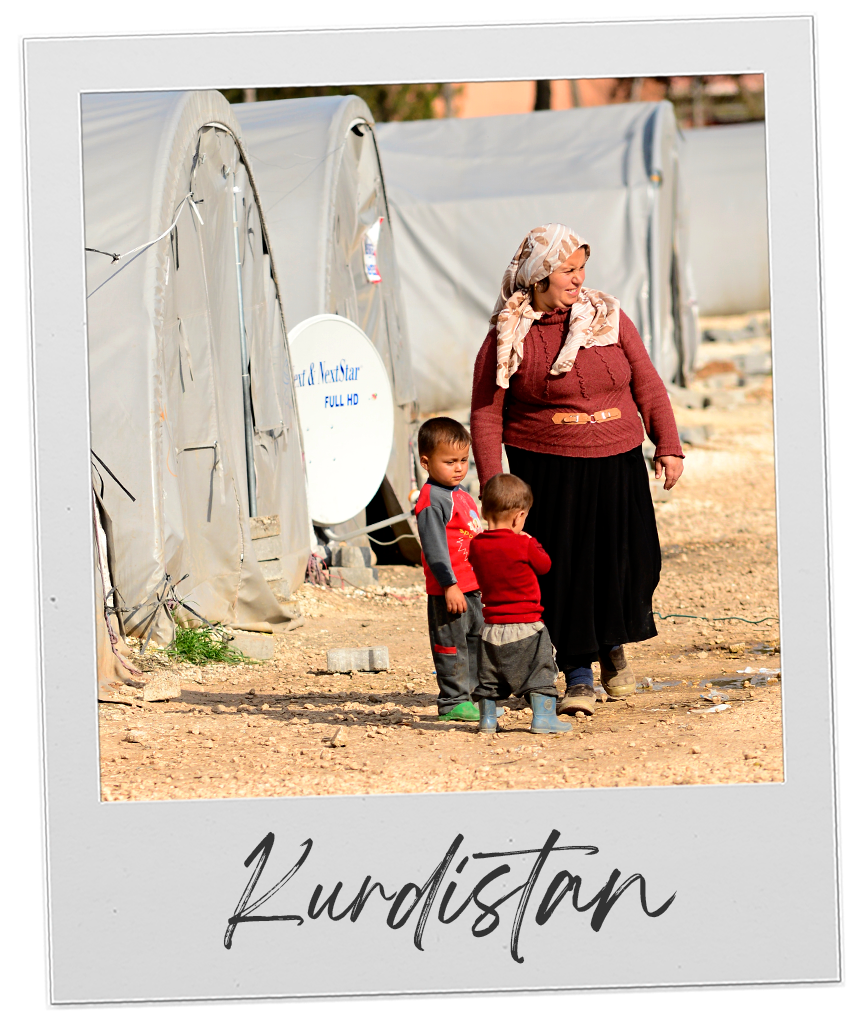

Socio-political dynamics in Kurdistan-Iraq remain unresolved. Kurdistan-Iraq has endured over 50 years of instability rooted in complex historical and socio-political dynamics, including issues of ethnic identity, control over natural resources and the Kurdish struggle for independence and self-governance. The semi-autonomous region of Kurdistan represented a significant step towards Kurdish self-governance. However, the path to stability has been hindered by internal divisions among Kurdish factions, disputes with the Iraqi central government over territory and oil revenues and external pressures from neighbouring countries concerned about Kurdish separatism. The rise and fall of the Islamic State added another layer of complexity, with Kurdish forces playing a key role in combating the group.

Many challenges remain in achieving gender equality and there is increasing backlash towards women’s rights and LGBTQI advocates in Kurdistan-Iraq. In contrast to many parts of Iraq and the surrounding region, there have been important legal reforms in relation to violence against women, family law, and political participation in Kurdistan-Iraq. However, progress has been uneven and faces cultural and institutional barriers and backlashes. Many challenges remain in establishing and sustaining meaningful gender equality, particularly in rural areas, and there has been a significant decline in international funding and attention towards gender equality in the region coupled with increased backlash and attempts to debilitate equality movements.

Labour and migrant workers

What we found

Variation

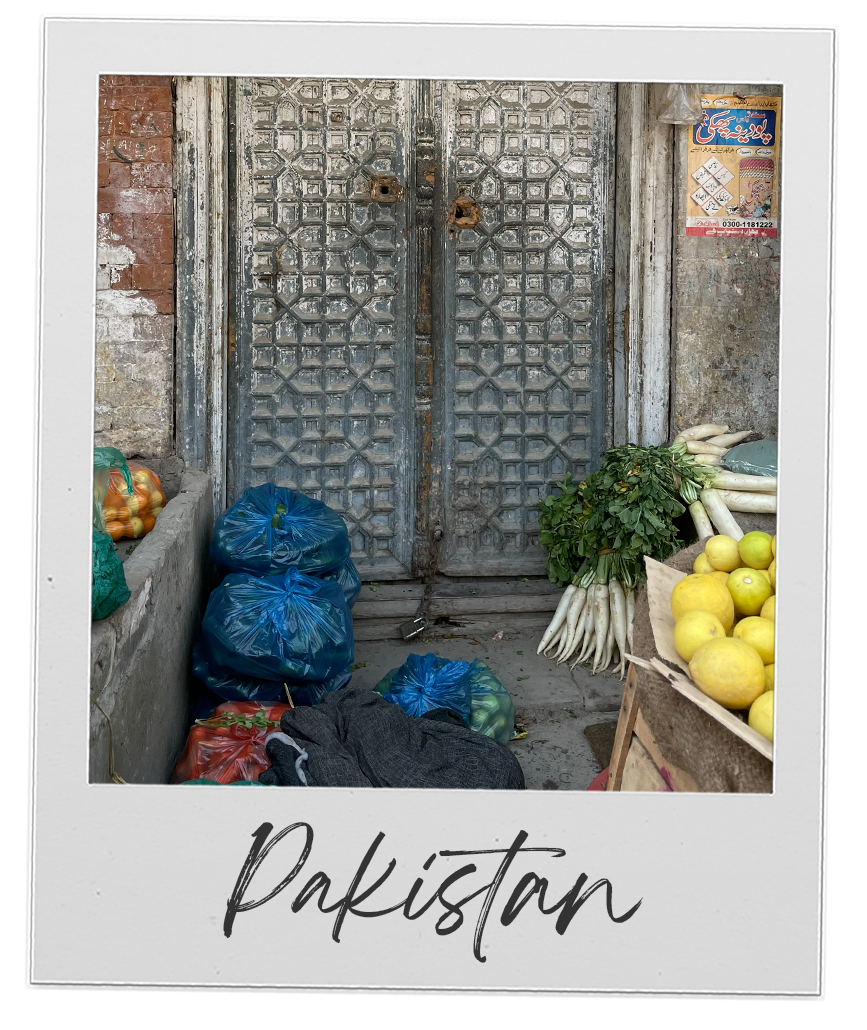

Migrant women in Kurdistan work in a variety of sectors and have a range of skills. Many work in households, hospitality, education (international schools and universities), beauty, NGOs, and business and have migrated from North America, Europe, Africa, South Asia and neighbouring countries in the Middle-East. South-South migration includes both highly educated and skilled women (Iran, Pakistan, South Africa, Syria), as well as less skilled waitresses and domestic workers (Ghana, Indonesia).

There are very different regulations of work. Service workers are regulated under the kafala system with a guarantor, while skilled workers have contracts with their employers. Refugees from neighbouring countries have the right to work granted by the KRI government. Among migrant domestic workers, salaries vary according to nationality with Filipinas receiving the most and African women the least. However, in general the women are satisfied with their income.

Challenges

There is a lack of overall protection for service workers. Regulation No 2 on Foreign Workers has not been updated since its inception in 2015, and does not take into account new issues such as COVID-19. Its impact varies according to type of work with many professionals in education and NGOs able to work online but leaving those in hospitality without work or income. Migrant domestic workers continue work but are often expected to do so even if ill. Professionals know their contract and how to raise issues; whereas some service workers have not received their contracts or know how to challenge their working conditions.

Sexual Harassment is a major challenge. Many of the women in this study complained about sexual harassment on public transport, especially taxis, and other public spaces, limiting their mobility and safety across the city.

Return and reintegration

What we found

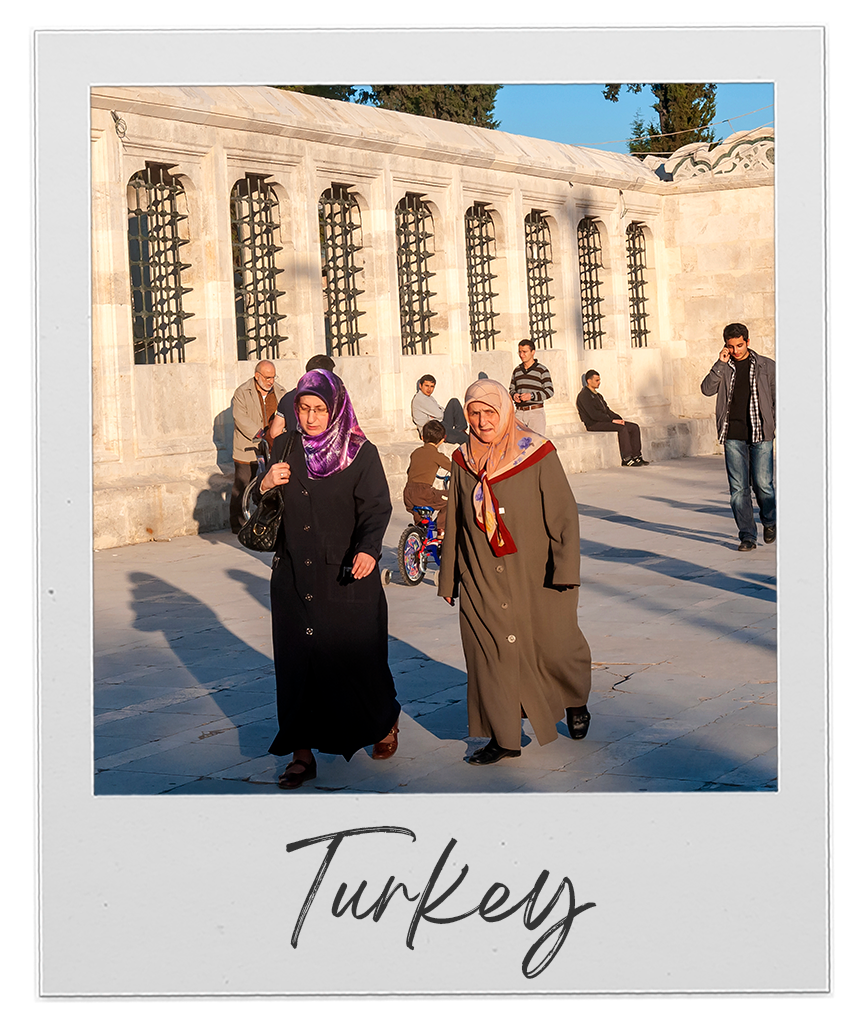

The Kurdish diaspora results from multiple and recurrent strategies of state-led demographic engineering and displacement to which the Kurdish communities in each of the four states (Turkey, Iran, Iraq and Syria) have been subjected. The Kurdish diaspora that began in the 1980s continued so that currently the Kurds not only constitute one of the largest stateless nations in the world, but also one of the largest diaspora communities.There is little comprehensive statistical data on the Kurdish population in Europe and existing data is conflated and confused because European countries register migrants according to their nationality, not their ethnic affiliations and therefore Kurds remain registered as ‘Turkish’, ‘Iranian’, ‘Iraqi’ and ‘Syrian’ when they arrive in Europe. This policy has not only subsumed Kurdish identity under an ethnic categorisation that does not distinguish Kurds from other minority ethnic groups, but it also imposes upon them an unacceptable national identity that most have spent their lives opposing.

Based on our fieldwork and a growing body of literature, we argue that the conflict generated Kurdish diaspora can be seen as a politicised, plural, and hybrid formation that has been shaped not only by the fundamental experience of statelessness, violence, and displacement in the country of origin but also by opportunities and difficulties in the Europe.

The emergent Kurdish diaspora is no longer a community of refugees. There are significant Kurdish professions and companies in Germany, Great Britain and Sweden. The Kurdistan Regional Government can benefit from the diaspora’s unique ideas, skills and resources to persuade them to invest economically and culturally in conflict affected Kurdistan. This could support Kurdistan’s economic diversification and help build transnational networks, strengthen ties between sending and receiving countries, and directly contribute to development efforts.

Neither Here Nor There – Return Mobilities (Documentary)

Resources

Gender and Forced Displacement in Humanitarian Policy Discourse: The Missing Link

This paper reports on a study that examines how gender has been referenced in United Nations (UN), supranational and state documents on forced migration over the past 40 years. It is motivated by the premise that humanitarian protection discourses reflect broader institutional priorities and ideologies and may therefore expose gaps that reveal the relative importance given […]

Neither Here Nor There – Return Mobilities

Migration is not a one-way street. Recent years have seen increasing transnational mobility and return migration, involving the rapid development of transport and communication technologies, the relative improvement of political and economic situations in the migrants’ homeland as well as anti-migration hostility and the exclusion of incoming people from the labour market in settlement countries. […]

Kurdistan-Iraq: Migration and displacement briefing

This brief focuses on both return migration to Kurdistan-Iraq from within the Kurdish community and global migration specifically to the city of Erbil in Kurdistan-Iraq. Little is known about the gendered elements of return migration to conflict-affected contexts, and how this relates to development, gender equality, justice and inclusive peace. Equally, there is work to […]

Return, Reintergration and Political Restructuring

Previous research on return migration has mainly covered return to political and economically stable countries. Furthermore, the literature predominantly focusses on economic reasons for return. Much less is known about the gendered experience of return migration to conflict-affected contexts, and how this relates to development, gender equality, justice and inclusive peace. This research project explores […]

Displacement, Diaspora and Statelessness: Framing the Kurdish Case

In this article, we draw on a growing body of literature and a set of empirical work carried out over a period of many years and through various projects to examine the characteristics of Kurdish refugee communities, concentrating on the triangular relationship between statelessness, displacement, and diaspora. By keeping our focus on these linked relationships, […]

Gendered Dynamics of International Labour Migration: Kurdistan Region, Iraq

This study is part of a larger multi-country research project ‘Gendered Dynamics of International Labour Migration’ involving four countries and main cities in them: Islamabad in Pakistan, Istanbul in Turkey, Beirut in Lebanon and Erbil in Kurdistan Iraq (KRI). The analysis aims to contribute to theoretical and empirical knowledge of gendered migrations, both within the […]

Kurdistan-Iraq Country Briefing

This brief on Kurdistan-Iraq from the Gender, Justice and Security Hub looks at the country context, including issues around unresolved tensions in the region, efforts for peace and autonomy, continuing security and political challenges, and gender equality and social development. The Hub projects in Kurdistan-Iraq explore complex social issues centred around gender dynamics, labour, and […]