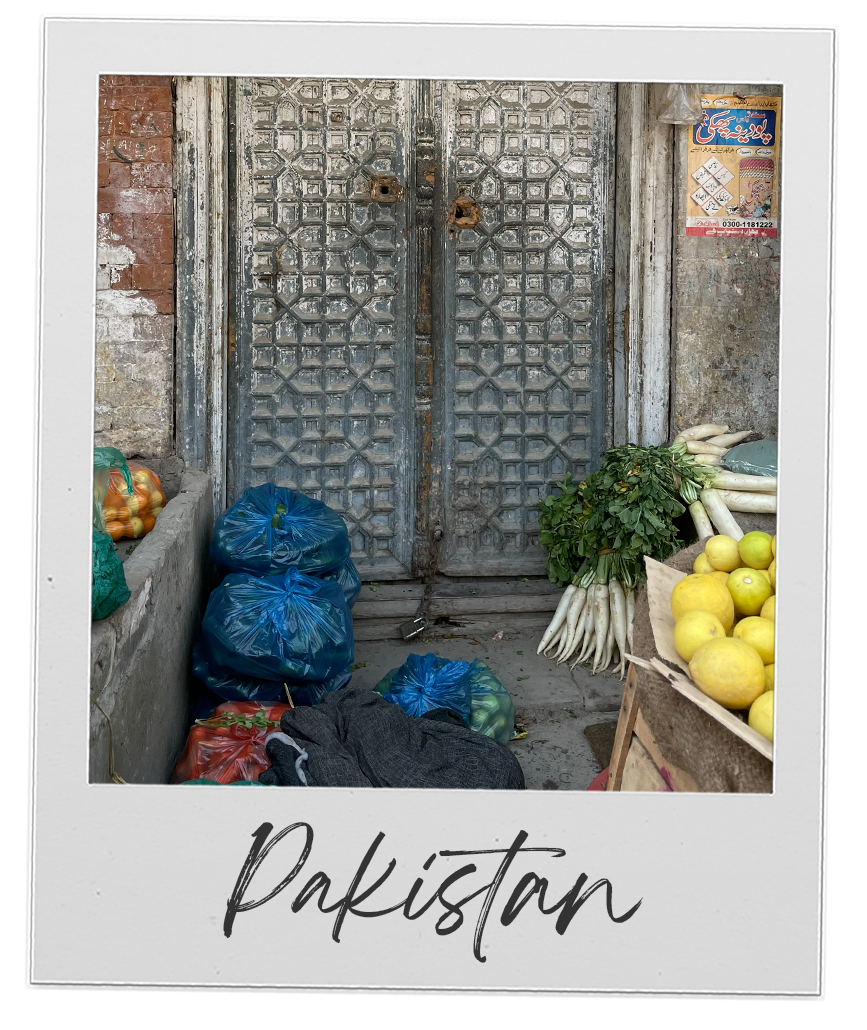

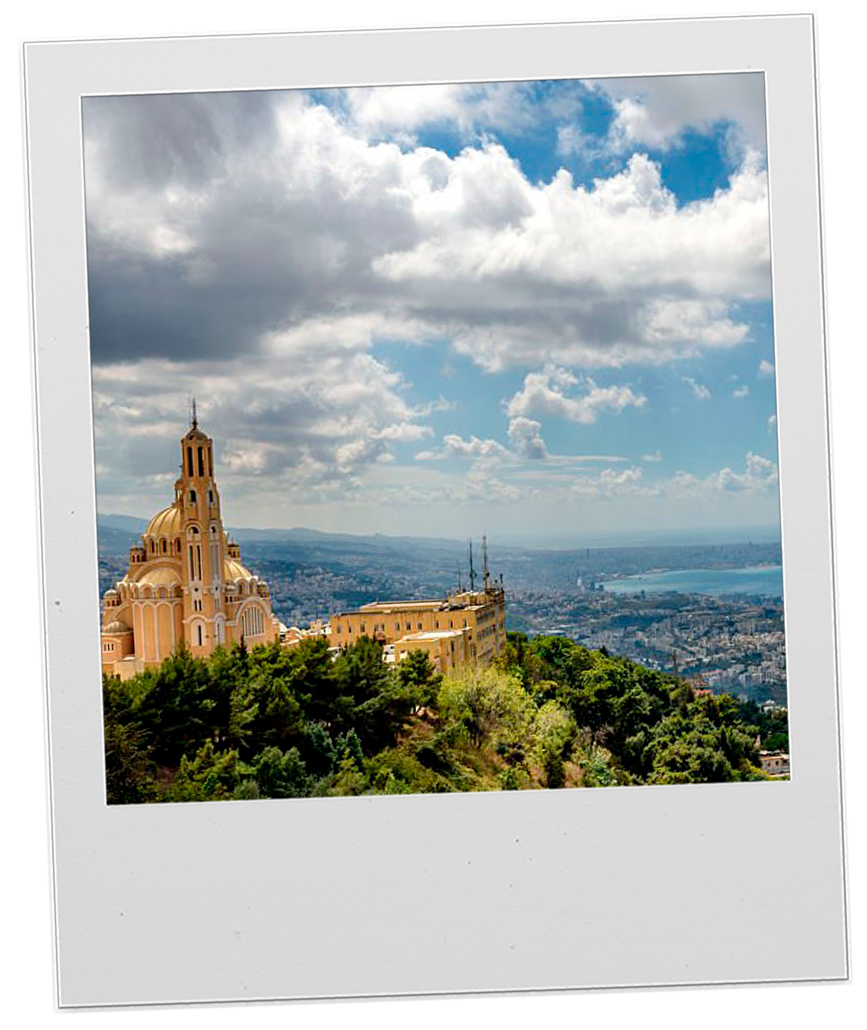

Lebanon

Migration and displacement

What we found

Labour and migrant workers

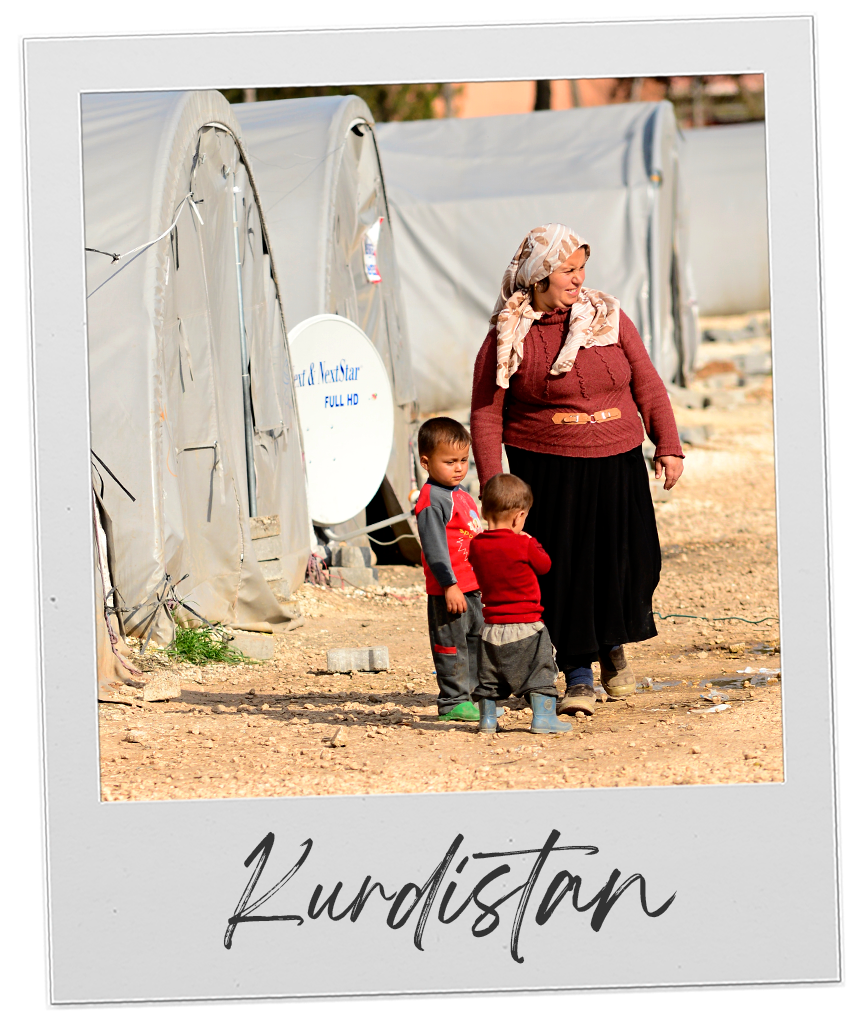

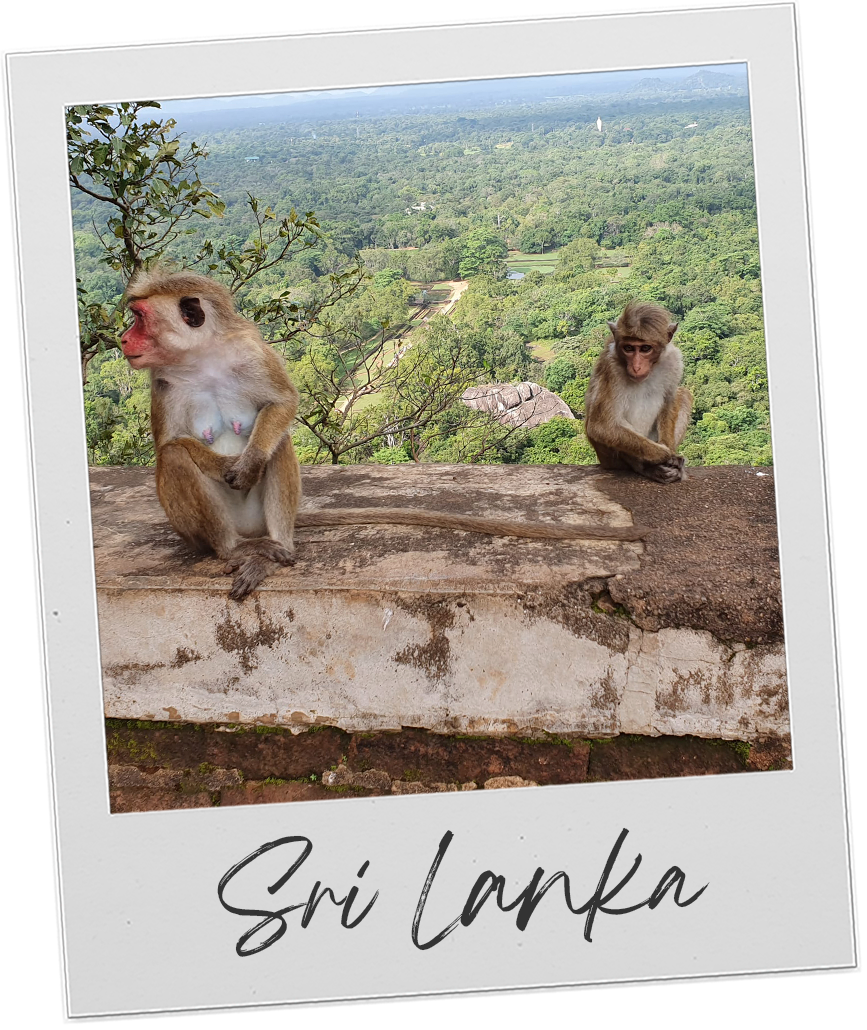

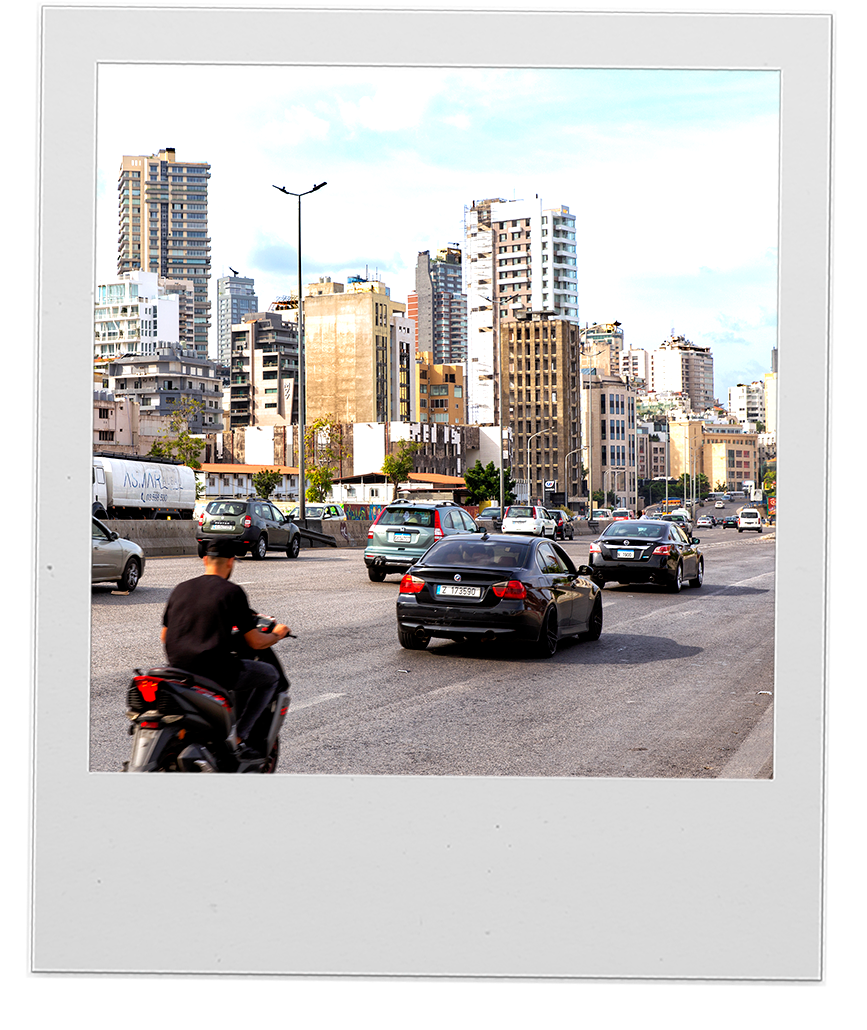

In 2020, the International Organization for Migration (IOM) estimated that the number of migrant workers in Lebanon exceeded 400,000. These workers come from countries like Bangladesh, Egypt, Ethiopia, Sudan, the Philippines and Sri Lanka and work in Lebanon to support their families through remittances. In relation to undocumented migrants, recent estimates calculated that Syrian refugees in Lebanon, at approximately 1.5 million, are more than one-quarter of the Lebanese population.

The research team interviewed 21 migrant women and three third sector practitioners in the greater Beirut area in Lebanon employed in a service active in the field of migration and gender. Twelve of the migrant women were migrant domestic workers, five were Syrian skilled professionals, and four were undocumented Syrians engaged, in sex work to varying degrees or unemployed. The interviews explored participants’ economic and socio-cultural drivers of migration, their living and working conditions and their experiences of the multiple crises Lebanon is facing.

Agency and independence

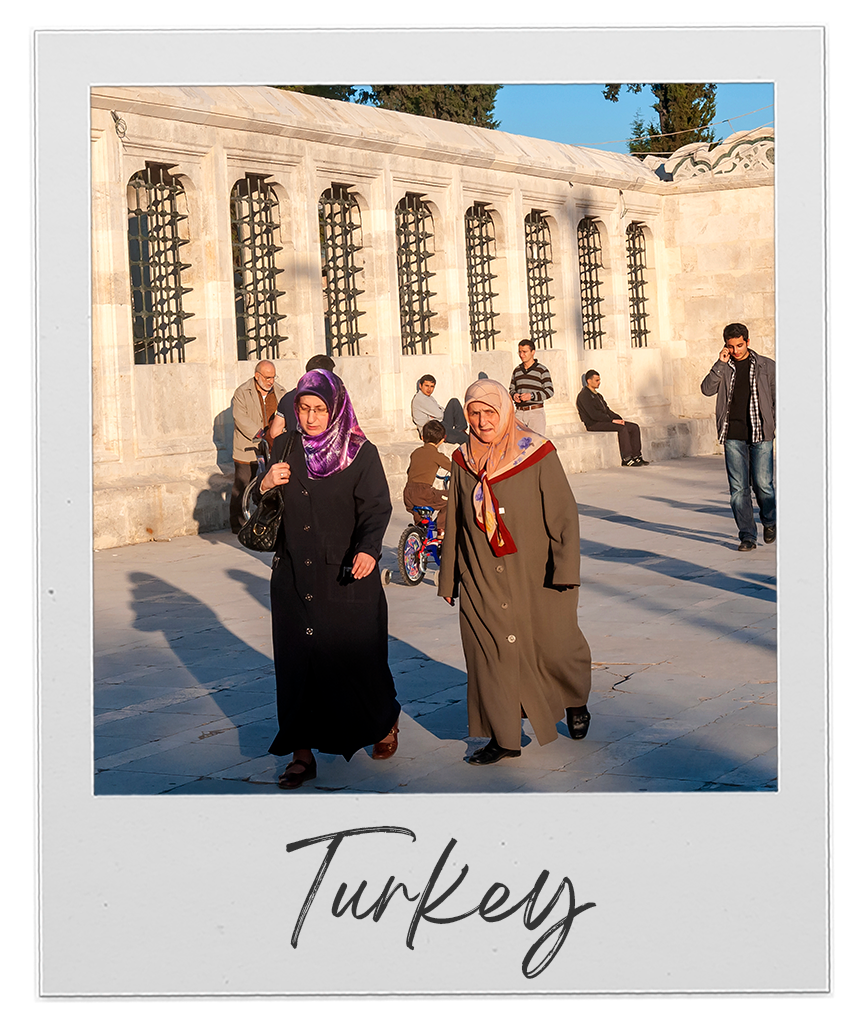

The migrant women we spoke to exhibited high levels of agency in their decision to migrate. Leaving behind unbearable conditions of discriminatory gender norms and/or familial and social gender-based violence, poverty and/or conflict-related hardships, was perceived as emancipatory and empowering. For domestic workers the choice of Lebanon as a destination was, to a great extent, pre-determined by the market of the recruitment agencies under the kafala system. Financial independence and being able to help their families were a source of pride. The five Syrian professional migrants were integrated into Lebanese society, but as second-tier citizens, suffering from structural discrimination. They were also the ones affected the most by the Lebanese triple crisis (economic collapse, COVID-19 and the August 2020 port blast).

The domestic workers perceived their experience in Lebanon as temporary, as is typical of circular migration. They did not seem to be on any pathways to integration in Lebanon. Many declared that they did not go to public spaces, had no social life and attended no social events. They spent their little free time on their phone, watching the television and talking to their family back home. The use of technology was a virtual place of freedom and empowerment.

For the sex workers (which included two refugee transwomen), being able to make, save and send money to their family gave them a sense of empowerment. Hope that they could change their condition coexisted with an attitude of acceptance, resignation and a self-denigratory attitude. These women did not find civil society groups supportive or understanding of their situation.

Challenges

In Lebanon there is a lack of legal and societal preparedness to respect and protect the rights of female migrant workers and refugees and to cater for their needs. Women migrant workers do not enjoy standard labour conditions, and suffer from social and institutional discriminations. National and international tools to protect female migrant workers are still insufficient.

Labour migration

What we found

- Women move to Lebanon to improve their life conditions. In relation to the migrant domestic workers, the migrant women show agency in their decision to migrate, motivated by a strong desire to change their lives. The choice of Lebanon as a destination is, to a great extent, pre-determined by the market of the recruitment agencies under the kafala system.

- Economic factors strongly influence migration. The main, self-reported driver for leaving home is that of finding either their first employment or a new one with a higher income. Poverty and restricted life prospects can be considered the main drivers of migration for migrant domestic workers. Being able to make, send and save money is a source of empowerment and pride, which appears to set a reassuring temporal limit to their stay in Lebanon, while also making their life conditions there more acceptable.

- Most women viewed their stay in Lebanon as temporary. The women are at a stage where they perceive their experience in Lebanon as temporary, as is typical of circular migration. Due to this, they do not seem to be on any pathways to integration in Lebanon. Many declared that they do not go to public spaces, have no social life and attend no social event, whereas they spend their little free time on their phone, watching television and talking to their families back home. The use of technology as a virtual place of freedom and empowerment emerges as an important phenomenon requiring further investigation.

- Agency, empowerment, and hope play key roles in women’s experiences with migration and marginalisation. The coping strategies of the four undocumented Syrian women, which includes two refugee transwomen, consist in the choices, actions, and narratives that can mitigate the hardships of their situations as undocumented migrants – for example, being able to make, save and send money to their family gives them a sense of empowerment. Plans for future migration endeavours are also signs of an orientation towards change. Further, one NGO practitioner provides a reading of hope when suggesting that the growing number of MDWs falling out of the exploitative kafala system might be the start of a bottom-up, freelancers-based alternative system to the kafala.

- Support-seeking remains challenging for women in migration contexts, particularly women who face intersecting forms of marginalisation. The case of the two refugee transwomen is important when looking at the dynamics of support-seeking. The support of the third sector is not considered very helpful by the participants. Nonetheless, seeking support is an important action of self-protection and coping with difficulties. The experiences of these women disclose also questions around the reputation of Lebanon as a country of freedom in contrast with a country where discrimination against different types of minority groups is instead widespread.

- Lebanon’s triple crisis (the economy, the Beirut port explosion, and Covid-19) has a disproportionate effect on migrant women. The NGO practitioners describe the impact of the triple crises on migrant domestic workers, as well as on undocumented migrants from Syria, as far more significant and devastating than the migrant women describe, who mainly suffer from increased isolation and reduced income. Echoing what has been mentioned above, the practitioners describe a scenario where the women are fired, not paid, and abandoned in front of their embassies. Many want to return home, face increased discrimination, hostility and sexual violence.

- Covid-19 has led to increases in gender-based violence. Looking at the wider migrant population, including the even more vulnerable undocumented migrant workers, the NGOs’ participants indicate that gender-based violence and the violation of sexual and reproductive health rights has considerably increased, whereas in-person support has become impossible.

Resources

Gendered Dynamics of International Labour Migration: Beirut, Lebanon

The historical and turbulent migration processes of Lebanon are reflected in a dynamic and composite country demography, including gender and labour features of migration. Currently, the number of migrant workers and refugees are exceptionally high in the country. Most migrants and refugees are women who live and work in unprotected conditions, making them vulnerable to […]

Lebanon Country Briefing

This brief on Lebanon from the Gender, Justice and Security Hub looks at the country context, including issues such as the ongoing unrest caused by the previous civil war as well as conflict in neighbouring countries, challenges with recovery, rebuilding and reform, and ongoing security challenges. Gender issues in Lebanon are complex; while there have […]