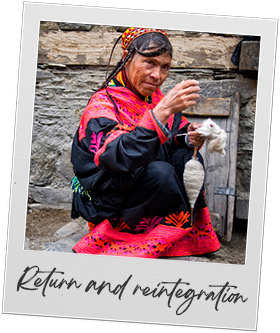

Return and reintegration

Research on return migration has mainly covered return to political and economically stable countries. The literature usually focusses on economic reasons for return. Much less is known about the gendered experience of return migration to conflict-affected contexts, and how this relates to development, gender equality, justice and peace. This research explores and analyses the gender experiences of returnees (forced and voluntary). It reviews return policies to understand the possibilities, challenges and obstacles for returnees in the process of participating in re-construction.

This research project explored the gender experiences of returnees (forced and voluntary) in Afghanistan, Kurdistan, Pakistan and Sri Lanka. It reviewed return policies of the countries under study to understand the possibilities, challenges and obstacles for returnees in the process of participating in re-construction through their human, social and cultural capital.

The research used a mixed methods ethnographic design including surveys and structured interviews with a total of 679 migrant participants with diverse levels of education, different destination countries, occupations, ages, and genders. In the Afghan context, this research was conducted in Kabul and Kandahar before the return of the Taliban in 2021, making it some of the last data gathered by researchers in country pre-Taliban.

Factors driving return migration in the host country include poor living conditions, racism, and discrimination (heightened during the COVID-19 pandemic), and improved or stable conditions in the origin county, which can make return either feasible, profitable or both. These factors include political, economic and social changes, access to personal relationships and personal resources, and the relevance of newly acquired skills to the country’s development priorities and integration policies. Many return to their homeland for jobs where they can use their skills learnt in their settlement countries, to contribute the economic and political stability of their post conflict homeland and participate in the job market.

Some refugees were not able to enter the formal education system in their settlement countries where refugees are often discriminated against. This was particularly the case for Afghan migrants who have left for Pakistan or Iran. Interestingly they returned to Afghanistan to seek further education (pre 2021 Taliban takeover).

The internet, particularly social media, has revolutionised how diasporas connect with their homelands. Diasporas now leverage social media for communication, mobilisation, and knowledge exchange across borders. For young migrants and families, these online platforms are particularly impactful. They facilitate communication, information exchange, and participation in diverse aspects of life back home. These virtual networks extend existing social capital, built on family and political connections, influencing return decisions and maintaining vital ties.

Young people can connect with potential employers directly, promoting professional and entrepreneurial opportunities. Virtual networks also strengthen relationships and pave the way for real-world connections, supporting job seeking, civic engagement, and building a sense of belonging in their homeland. However, challenges remain. Unequal power dynamics and disparities in access to information can hinder truly inclusive participation.

Skilled returning migrants, especially women, are comparatively younger, better educated and able to commute between countries of origin and countries of settlement. Most returnees find a job that matches their level of education, for example in public administration, the health, education and IT sector or social services. Moreover returnees are often regarded as cross-border intermediaries whose ties to foreign resources and familiarity with their homeland institutions enable them to bring innovative practices to organisations in their countries of origin.

Together with their economic, cultural and political remittances, direct investments, the transfer of knowledge and technology of the host country, and skills and training, returnees are successful in using their human, social and cultural capital. Despite female returnees facing more discrimination based on their gender, lifestyle, political views, ethnicity and age, they play a crucial role in the fight for gender equality and contribute to peace and development.

Despite numerous studies indicating that only men return to their homeland, this study finds that women return just as frequently. Women are returning to their homeland to be part of the political process and contribute to the economic development of their homelands where they often hold roles in higher education, with 40% of respondents working in education, public administration, finance and health. In addition to this, across all four countries, women returnees have higher education levels than men. Crucially, women use their roles within public and private spaces to contribute to gender equality policies and are very active in advocating for gender equality. This is the case particularly for Kurdistan-Iraq and Afghanistan.

People face barriers to returning, for example a limited labour market, large salary differences between the settlement country and their homeland, and a lack of returnee policies that would give access to housing, education programmes and entrepreneurship programmes for example. This means that many young people who are able to contribute to peace and economic development are unable to return.

Some returnees feel alienated from their homeland due to language barriers and/or because of competition between returnees and local people.

Some local people resent return migrants, claiming they do not understand the traumas the nation experienced during the conflict. Furthermore, returnees are accused of leaving the country during conflict and only returning to exploit the job market in the relatively prospering post-conflict transitional period.

Resources

Sri Lanka country briefing – Gender Migration Culture

This brief focuses on two separate but interconnected aspects of post-conflict Sri Lanka. Firstly, the brief looks at the current realities for returning migrants and internally displaced persons (IDPs) in the Jaffna District in the Northern Province, one of the areas where there is a large IDP population. The findings show how gender and intersecting […]

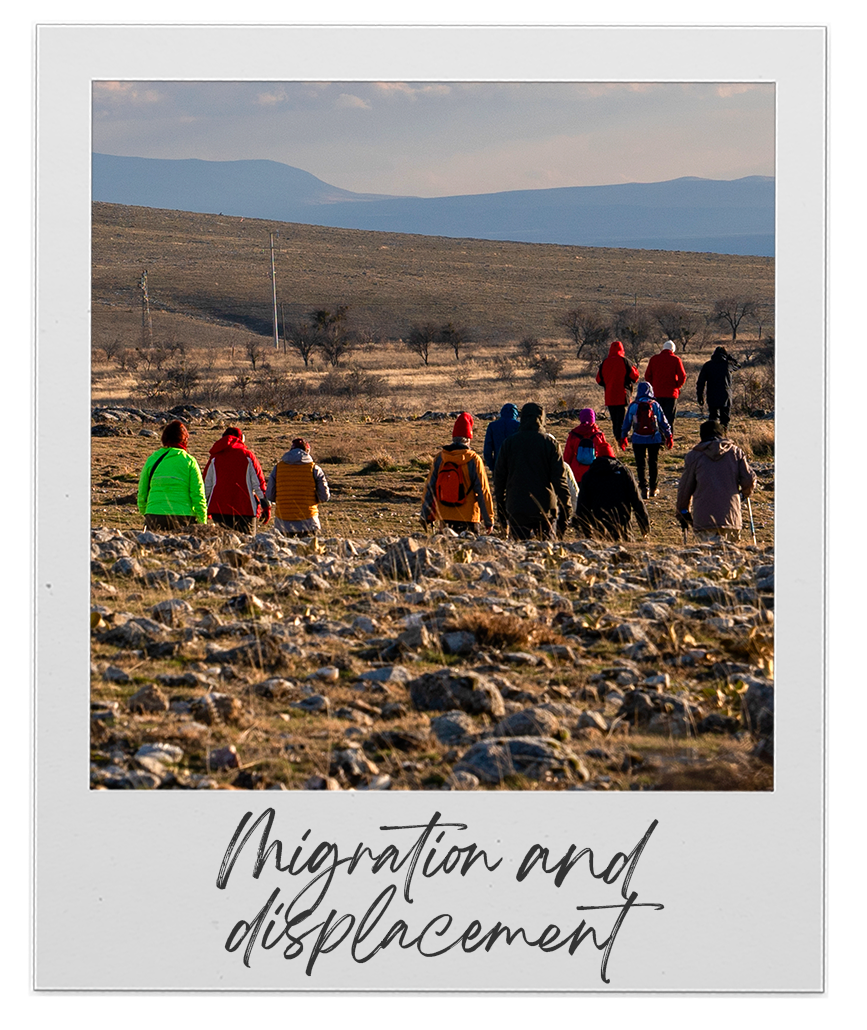

Kurdistan-Iraq: Migration and displacement briefing

This brief focuses on both return migration to Kurdistan-Iraq from within the Kurdish community and global migration specifically to the city of Erbil in Kurdistan-Iraq. Little is known about the gendered elements of return migration to conflict-affected contexts, and how this relates to development, gender equality, justice and inclusive peace. Equally, there is work to […]

“I was born here”: Children’s participation and refugee education in Pakistan

Over the last four decades, there have been several waves of movement across the borders due to recurring conflict in Afghanistan, as well as internal displacement within the country due to conflict and natural disaster. Pakistan remains one of the five largest refugee-hosting countries in the world; as of June 2022, an estimated 1.3 million […]

Displacement, Diaspora and Statelessness: Framing the Kurdish Case

In this article, we draw on a growing body of literature and a set of empirical work carried out over a period of many years and through various projects to examine the characteristics of Kurdish refugee communities, concentrating on the triangular relationship between statelessness, displacement, and diaspora. By keeping our focus on these linked relationships, […]